Since O negative blood is considered the universal blood type, you might be surprised to learn that O positive is the blood most given to patients in an emergency when their blood type is unknown.

Why is this? There are a number of factors, including basic blood group science, hospital use and policies, trauma triage, probability, and logistics.

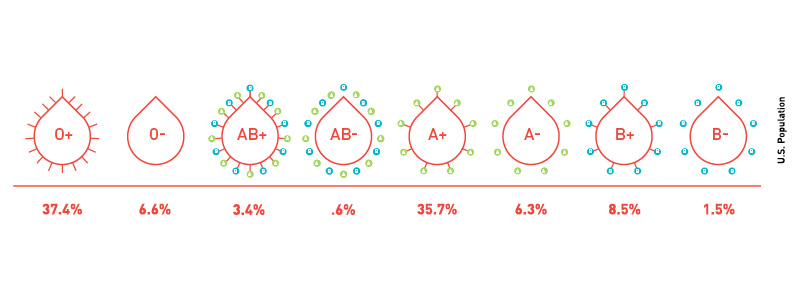

Type O is the most common, and most transfused, ABO blood type in the US: 48% of Americans have type O blood.

A unit of red cells from a group O blood donor is considered the universal type in terms of the ABO blood group system. This is because there are no A or B sugars on the surface of a group O red cell for ABO antibodies in a recipient’s circulation to bind. If there were, the cells would be destroyed and the recipient would react to the transfusion.

| Patient ABO type | ABO antibodies in circulation | Compatible red cells |

| O | Anti-A and anti-B | O only |

| A | Anti-B | A or O |

| B | Anti-A | B or O |

| AB | none | O, A, B, or AB |

However, ABO is just one of many different blood groups. The most well-known of these other blood groups is Rhesus (Rh), but the list includes Kidd, Kell, and 31 other major blood group systems.

If a patient has had opportunity to make an antibody against one of these blood groups, through pregnancy or prior transfusion, then their body might still react to a group O red cell.

The difference is that ABO reactions are present in the body from birth, before exposure, while reactions to the other blood groups come after exposure.

The vast majority (99%) of patients receiving donated blood on any given day do not have red cell antibodies other than the naturally occurring ABO antibodies.

The Rh blood group system actually involves many Rh proteins, but the RhD protein rises to the top of importance with transfusion. When we refer to a donor or patient as Rh positive, we are referring to the fact that the RhD protein is expressed on their red cells. An RhD negative blood donor lacks the D protein.

The D protein is large, so the immune systems of healthy RhD negative people transfused with RhD positive cells can easily detect D and might consider it to be foreign (and therefore something to be destroyed).

Unlike naturally occurring ABO antibodies, red cell antibodies against the RhD protein are formed after exposure. A patient transfused with RhD positive cells might develop the anti-D, but this is not guaranteed. In fact, studies show that only about 40% of RhD negative patients will make an anti-D.

Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) due to Rh incompatibility is present in anywhere from 0.003 to 0.08% of pregnancies and used to cause significant numbers of fetal death during pregnancy prior to the development of RhD immune globulin, a medication used to treat Rh incompatible pregnancies. HDFN can occur when an RhD negative birth parent, who has made anti-D through prior exposure, is carrying a baby who has inherited the D antigen from the other, RhD positive parent. The birth parent’s anti-D can bind and destroy fetal cells, resulting in life-threatening anemia in the baby. ABO incompatibility doesn’t typically cause issues during pregnancy because of the nature of ABO antibodies.

With modern medical advances, particularly the implementation of Rh Immune globulin administration during pregnancy, most RhD positive babies are born to RhD negative birth parents healthy and without any signs of HDFN. In the setting of emergent transfusion, in order to avoid sensitization to the D antigen, females of child-bearing age are given type O RhD negative transfusions in emergencies when their blood type is unknown.

Even though the percentage of group O patients in a hospital will be about 48% (the normal distribution in the population), a hospital will ask for more than 48% of its blood bank inventory to be group O.

There are a few reasons for this.

In an emergency situation where a patient needs blood and their blood type is unknown, group O is issued. The clinical team draws and sends a sample to the transfusion service to determines the patient’s ABO type as soon as possible so that ABO-type specific blood can be used to preserve the universal donor supply. This takes time, so type O cells are transfused to start the resuscitation.

Due to safety rules implemented by regulatory agencies, group O blood is to be issued until the laboratory has been able to determine the ABO type using two different samples drawn from the same patient. If the second sample is delayed in being drawn or sent to the laboratory, the transfusion service must issue group O cells.

The banked supply of very rare units – for patients with difficult-to-find red cells from those 30+ other blood groups – is most often group O. Since the lab supplying these units cannot predict what a patient’s ABO type will be ahead of time, it is easiest to stock and freeze very rare units that are group O but negative for rare antigens from different blood groups. An example would be a group O unit that is negative for the Kidd3 antigen; this red cell is typically only found in blood donors of Asian or Polynesian descent. It would be needed in a Kidd3-negative recipient who has developed anti-Kidd3 antibodies against other peoples’ red cells.

Newborn babies who require a blood transfusion are typically supported with group O red cells. This is in line with unknown blood type in an emergency, as the determination of ABO type in a newborn can be more challenging than in an older patient.

The natural incidence in the population is that 85% of people are RhD positive; 15% are RhD negative. When including ABO type in this, only 7-9% of the population is group O RhD negative.

It is impossible to support 100% of the trauma population with only 9% of the community supply, especially when inventory is already low due to seasonal dips in the supply and an aging donor population.

Because of the rarity of the O negative blood supply, hospital and blood center policies reserve emergency O negative red cells for children and females of child-bearing age.

Fortunately, the chance that this will be an issue for other patients is low — and backed by probability:

First responders may transfuse badly injured patients before they arrive at the hospital, such as in the ambulance or life-flight helicopter. Studies show that for particular injuries, such as chest injuries, pre-hospital transfusion can save lives.

Bloodworks supplies group O whole blood for this purpose.

While we collect whole blood at donor centers and mobile drives, it’s typically processed into separate components prior to transfusion.

Because of space and weight limits in emergency vehicles, it may be preferable to give a whole blood unit rather than separate packed red cell and plasma units.

In this case, the whole blood is always RhD positive. Since whole blood has a shorter shelf life than packed red cells, RhD negative packed red cells are better utilized for their full shelf life as a way to have more supply for the entire community.

If an RhD negative woman of child-bearing age were to receive the whole blood, there is a protocol to administer a very large dose of Rh immune globulin following the trauma resuscitation in an effort to prevent the formation of anti-D. The goal of saving the patient’s life is the priority over saving a future case of hemolytic disease of the newborn.

This practice is not without controversy, but producing an inventory of RhD negative whole blood -and ensuring its appropriate use- has proven impractical.

Bloodworks’ O donors save lives and stabilize trauma victims. O blood donors go the extra mile by supporting O patients and patients who urgently need a lifesaving transfusion. But as soon as the patient’s ABO type is known, the laboratory changes transfusion support to the patient’s ABO type. This is the best stewardship of the supply. Having all types on the shelf helps to ensure we do not deplete either the universal supply, or the type specific supply.

Tell Us What You Think!